You might think what I’m about to describe is something that just a few young, lively going-out types are into, or a gimmick for tourists. You’d be wrong. First of all, pretty much everyone in Spain goes out all the time, as I’ve made clear in previous posts. Secondly, pretty much everyone in the Basque Country – of all ages and classes – goes out for ‘pintxos’. Every bar and café in every city, town and village serves ‘pintxos’.

In Britain, people go out for beer, possibly accompanied in a rather incidental sort of way by some rather paltry crisps or nuts. Here, the drink is incidental: it’s the food that matters, and it’s what forms the focus of going out.

‘Pintxos’ are similar to ‘tapas’ in both content and function, and yet different in some significant ways: it’s quite complicated to explain – but I’ll try….

Like a ‘tapa’, a ‘pintxo’ is a small snack that you have with a drink or before a meal. However whereas a ‘tapa’ is a very small bowl of one specific dish - e.g. a handful of ‘aceitunas’ (olives) or a few fried ‘pimientos’ (peppers), or a few spoonfuls of ‘patatas bravas’ (spicy tomatoey potatoes) or a few ‘albondigas’ (meatballs) – a ‘pintxo’ is an assemblage of food presented on a small piece of bread and (usually) held together with a cocktail stick or toothpick (a ‘pincho’ in Spanish). Imagine something like a large-ish elaborate canapé, and you’ve sort of got the picture.

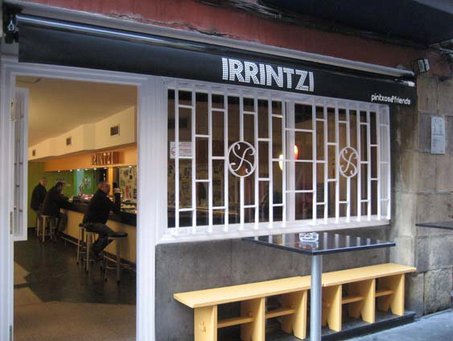

That makes it seem simpler than it is. On a Friday or Saturday night, or at lunchtime on Saturday or Sunday, there is usually a huge crush around the bar with dozens of people trying to indicate what kind of ‘pintxo’ they want, as well as order drinks. There might be as many as 20 or 30 different ‘pintxos’ to choose from, and every bar has its own specialities, many of which can’t be found anywhere else. In keeping with the general tenor of social life in Spain, it’s a quite high energy and ‘in your face’ business – noisy and crowded, and even a bit stressful (though in a good way).

Then there’s the whole business of deciding who does the ordering and paying. If you don’t know what you’re doing, you all have to study what’s on offer and tell the bar-person what you want individually, which slows everything down and crowds the bar: much more sensible to put one person in charge of getting the ‘pintxos’ in each bar. And as for paying – there can’t be any ‘going dutch’: far too complicated. Apparently, the Basques often pool their money at the beginning of the evening, creating a kitty from which to draw. Paying happens at the end, when you’ve finished. You tell the bar-person how many pintxos you’ve had and they tot up the total: they’re usually an extraordinarily cheap 1.5 Euros (£1.20) each.

And the group of friends you do the ‘txikiteo’ with on Saturday night is no random group of friends: it’s your ‘cuadrilla’, a group you’ve been part of since you were at school. (Most people in Spain stay in the town of their birth: moving away for university or work is not as common as it is in the UK.) Many ‘cuadrillas’ are single-sex, it seems. If you’re married, you and your wife are likely to be going out separately, in two different ‘cuadrillas’.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed