From Paris, the train takes 3 hours to reach Bordeaux, then another 2 hours to reach the little Pays Basque, in the deepest south-west corner of France. From there, it winds slowly for an hour along the small stretch of the Basque coast to Spain, going through Bayonne (the main city of the Pays Basque), past Biarritz, Getaria and Saint Jean de Luz, and ending up in the border town of Hendaye. There one enters Spain and boards a ‘Euskotren’ to Bilbao.

We’d had some tantalising glimpses of the French Basque coast on our train journeys to and from England, so, after our trips to Santander and Hondarribia (see previous post), we spent a couple of days there, curious to see how Basqueness translated from Spain into France. Unfortunately the weather was pretty terrible, so we didn’t see the place at its best.

We started at the northern end of the Basque coast, in Bayonne (Baiona in Basque), a beautiful city with an imposing, if rather plain, Gothic cathedral, and lots of medieval character:

We’d had some tantalising glimpses of the French Basque coast on our train journeys to and from England, so, after our trips to Santander and Hondarribia (see previous post), we spent a couple of days there, curious to see how Basqueness translated from Spain into France. Unfortunately the weather was pretty terrible, so we didn’t see the place at its best.

We started at the northern end of the Basque coast, in Bayonne (Baiona in Basque), a beautiful city with an imposing, if rather plain, Gothic cathedral, and lots of medieval character:

Immediately, it was clear that French culture and language were dominant here in a way that Spanish culture and language aren’t (by and large) in the Spanish Basque country: there were shops, cafes and so on with Basque names, but relatively few. Unsurprisingly, Basqueness here had more of a French feel than in Spain, too. The food was quite different, with a distinctly French style. The architecture too was quite different, again rather French in style.

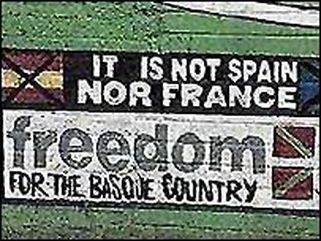

Still, there were substantial signs of Basque life here. A lot of people looked distinctively Basque, and the old town had the same slightly gritty and down-at-heel feel of most Basque old towns, with the usual Basque political graffiti in evidence:

Most of all, there was a really excellent Basque museum, covering the history, archaeology, art, language and culture of the Basques. And we even found one of the only two or three ‘makila’ makers left in the whole Basque Country. (A ‘makila’ is a Basque shepherd’s walking stick, made of medlar and often elaborately carved, which has a hidden blade in its base so that it doubles as a kind of spear. They are highly prized, often handed down from generation to generation, and often presented to people to honour them on special occasions.)

We discovered some wonderful cheeses from the Pyrenees, and the herbal liqueur of the Pays Basque, ‘Izarra’:

We also encountered the chocolate of Bayonne, famous because it was to Bayonne that chocolate was first brought to France, by Jewish ‘chocolatiers’ who had fled the Spanish Inquisition in 1492. A number of distinguished chocolatiers still exist in the town…

… and there is still a Jewish community here:

Our visits to Biarritz and Saint Jean de Luz were much briefer, and extremely wet.

Biarritz is a busy, sprawling seaside resort, fashionable (although not the height of fashion that it was a few decades ago) and not terribly attractive, with hardly any discernible Basque character, but a few grand 19th century buildings, and one or two atmospheric corners that indicate its past as a fishing port:

Biarritz is a busy, sprawling seaside resort, fashionable (although not the height of fashion that it was a few decades ago) and not terribly attractive, with hardly any discernible Basque character, but a few grand 19th century buildings, and one or two atmospheric corners that indicate its past as a fishing port:

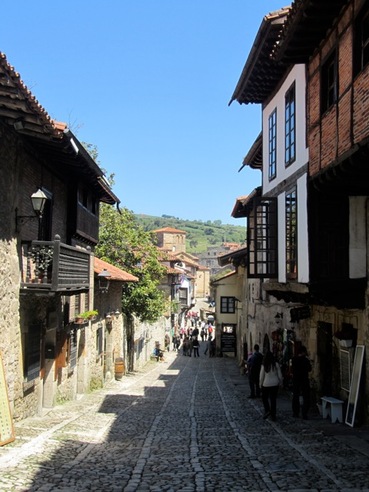

Saint Jean de Luz (Donibane Lohizune in Basque), on the other hand, is a very pretty and atmospheric little town with considerable character, though somewhat over-run by tourists. We were there for three hours and it rained non-stop and heavily for the entire time, so we weren´t able to appreciate it at its best. However, we managed to get a good feel for its distinctively French-Basque style of domestic architecture, and noted that aspects of Basque language and culture were more in evidence here:

It turned out that the town also had royal connections, since Louis XIV married Teresa of Spain here in 1660, and there are some rather grand houses where royalty stayed:

Of course there´s a lot more to the Pays Basque than this little stretch of coast, however pretty it is. By all accounts, the most interesting part of the Pays Basques – and by far the most Basque part – is the mountainous inland part in the Western Pyrenees – the towns of Pau and Saint Jean Pied de Port and so on. We didn´t have time to get there, unfortunately.

Here on the coast of the Pays Basques, Basque culture and language seemed largely to be little more than a tourist curiosity in a way that we have not encountered anywhere in the Spanish Basque Country – perhaps because there is nothing like the volume of tourism in the Spanish region that we encountered here on the French coast. There’s no doubt that the experience would be more quintessentially Basque in the Pyrenees.

But there’s also no doubt that Basqueness is not as big a deal in France as it is in Spain. Whilst there is some Basque nationalism in France (and, for instance, many Spanish ETA fugitives have found refuge in France) it´s not anywhere near as widespread as it is in Spain. Unlike the Basque Country in Spain, of course, the Pays Basque has no political autonomy: indeed, it does not even constitute a region of France, being only a part of the department of Pyrenees-Atlantique. There is no government policy to have Euskara taught in schools, and so on.

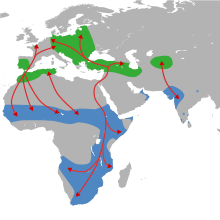

In Basque, the Pays Basque is referred to as ‘Iparralde’ – the North Country – whilst the Spanish side is ‘Hegoalde’ – the South Country – and of course many in the Basque country would like the north and south to be united. This is often expressed as '4+3 + 1" (4 Basque provinces in Spain plus three Basuqe provinces in France = 1 Basque Country). Anyone desiring to see a united, independent, cross-border Basque Country is likely to have some time to wait, though.

Here on the coast of the Pays Basques, Basque culture and language seemed largely to be little more than a tourist curiosity in a way that we have not encountered anywhere in the Spanish Basque Country – perhaps because there is nothing like the volume of tourism in the Spanish region that we encountered here on the French coast. There’s no doubt that the experience would be more quintessentially Basque in the Pyrenees.

But there’s also no doubt that Basqueness is not as big a deal in France as it is in Spain. Whilst there is some Basque nationalism in France (and, for instance, many Spanish ETA fugitives have found refuge in France) it´s not anywhere near as widespread as it is in Spain. Unlike the Basque Country in Spain, of course, the Pays Basque has no political autonomy: indeed, it does not even constitute a region of France, being only a part of the department of Pyrenees-Atlantique. There is no government policy to have Euskara taught in schools, and so on.

In Basque, the Pays Basque is referred to as ‘Iparralde’ – the North Country – whilst the Spanish side is ‘Hegoalde’ – the South Country – and of course many in the Basque country would like the north and south to be united. This is often expressed as '4+3 + 1" (4 Basque provinces in Spain plus three Basuqe provinces in France = 1 Basque Country). Anyone desiring to see a united, independent, cross-border Basque Country is likely to have some time to wait, though.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed