‘Zorionak’ = Season’s Greetings

‘Olentzero’ = the Basque Father Christmas

It’s December 25th and we’re off this afternoon to Italy and the UK for a couple of weeks, so here’s a last post before we leave.

‘Olentzero’ = the Basque Father Christmas

It’s December 25th and we’re off this afternoon to Italy and the UK for a couple of weeks, so here’s a last post before we leave.

Dec 21 - Santo Tomas

Christmas festivities begin properly here on December 21st with ‘el dia de Santo Tomas’, St Thomas’s Day, on December 21st. This is the major winter fiesta throughout the Basque Country, and is celebrated in the usual style here in Bilbao – with the population out in the town in force and plenty of music, eating and drinking in the streets. Many people dress in traditional Basque costume, rather as the Scots might go out for a boozy night out in kilts and other traditional garb. (As I’ve mentioned before, there are lots of parallels between the nationalism of the Scots and the Basques). (NB: Following a computer disaster, I lost all my photos of Santo Tomas, so have had to find appropriate replacements from the internet...)

Christmas festivities begin properly here on December 21st with ‘el dia de Santo Tomas’, St Thomas’s Day, on December 21st. This is the major winter fiesta throughout the Basque Country, and is celebrated in the usual style here in Bilbao – with the population out in the town in force and plenty of music, eating and drinking in the streets. Many people dress in traditional Basque costume, rather as the Scots might go out for a boozy night out in kilts and other traditional garb. (As I’ve mentioned before, there are lots of parallels between the nationalism of the Scots and the Basques). (NB: Following a computer disaster, I lost all my photos of Santo Tomas, so have had to find appropriate replacements from the internet...)

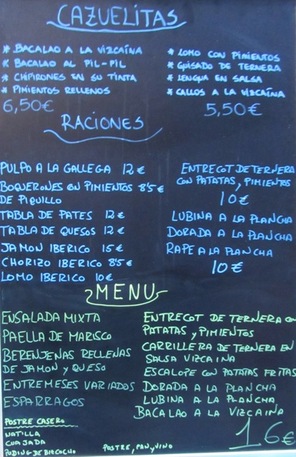

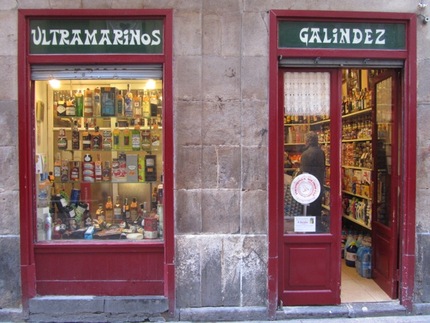

By now you won’t be surprised to learn that a major theme of the day is food. The streets around the Casco Viejo are lined with stalls (‘txosnas’) – around 250 in all – forming a huge ‘mercado rural’ – a farmer’s market – selling delicious food from the ‘baserris’ (farmhouses) in the countryside around Bilbao – fruit, vegetables, bread, cake (especially ‘Pastel Vasco’ – ‘Basque Cake’), meat, cheese, cider and so on. There’s also lots of mistletoe for sale. There’s a real sense of the countryside coming to town, a tradition that stretches back to medieval times.

On Santo Tomas everyone eats ‘talo y xistorra’. ‘Talo’ is a kind of soft floury flatbread similar to a Mexican ‘tortilla’, but a bit heavier. ‘Xistorra’ (pr. ‘chistorra’) is a sort of mild spicy sausage, essentially a fresh ‘chorizo’ that needs to be cooked before eating. On the day, the combination is sold to thousands from stalls all over the Casco Viejo, with the ‘talo’ cooked on hotplates and the ‘xistorra’ fried in big pans. And everyone drinks cider (‘sidra’) – always popular here, but this marks the beginning of the cider season.

You take your ‘talo y xistorra’ and your bottle of ‘sidra’, find a space with your friends, and ‘hang out’. And then you ‘hang out’ a bit more, possibly finding a bar and moving on to some wine or beer. The streets of the Casco Viejo are crammed, in fact, from about midday onwards, with thousands of people ‘hanging out’ and drinking until the early hours of the morning. You can hardly move there are so many people. People may get a bit tipsy but there’s no serious drunkenness, and it’s a nice atmosphere.

We spent the day ‘hanging out’ with some of Pietro’s work colleagues, who include a few Basques, a Catalonian, a Cantabrian, a Russian, an Estonian, a Dutchman, a couple of Poles, an American, and a Colombian: a typically international ensemble of research scientists….

Here's a video of the event from the Basque TV channel:

http://www.eitb.com/en/video/detail/1207250/video-bilbao-donostia-celebrate-santo-tomas-fair/

We spent the day ‘hanging out’ with some of Pietro’s work colleagues, who include a few Basques, a Catalonian, a Cantabrian, a Russian, an Estonian, a Dutchman, a couple of Poles, an American, and a Colombian: a typically international ensemble of research scientists….

Here's a video of the event from the Basque TV channel:

http://www.eitb.com/en/video/detail/1207250/video-bilbao-donostia-celebrate-santo-tomas-fair/

Dec 23 – The Arrival of Olentzero

On Christmas Eve, children leave their shoes by the Christmas tree and overnight Olentzero, the coalman, comes down the chimney and leaves presents for them, by their shoes. If they don’t behave themselves, they will only get a lump of coal. Images of Olentzero have appeared all over the place in recent weeks. Here are a few from local shop windows and houses:

On Christmas Eve, children leave their shoes by the Christmas tree and overnight Olentzero, the coalman, comes down the chimney and leaves presents for them, by their shoes. If they don’t behave themselves, they will only get a lump of coal. Images of Olentzero have appeared all over the place in recent weeks. Here are a few from local shop windows and houses:

Olentzero is far more than a Basque version of Father Christmas. Contemporary manifestations of Olentzero seem to represent a merging of the Christian and Basque traditions, but Olentzero’s roots are in the ancient traditions of Basque mythology – which has more in common with, say, the Celtic tales of pre-Christian Britain than with Christian sacred tradition.

There are several different versions of the Olentzero story, but basically he is said to be one of the ‘jentillak’, the giants of the Pyrenees which are at the core of Basque mythology – along with the mountain-men – ‘basajaunak’, the river-maidens – ‘lamiak’, and the mountain goddess Mari (probably no direct relationship to the Christian Mary, by the way). Interestingly, the word ‘jentillak’ has the same origins as the word ‘gentiles’ – meaning pre-Christian. It is now thought by many that the Basques may have been here in the foothills of the Pyrenees since the Stone Age, and the jentillak are said to be the mountain giants who built the dolmens and other ancient structures in the Basque mountains. They eventually disappeared, leaving only Olentzero behind. Olentzero then left the mountains and became a Christian, earning his living as a coalman / charcoal-burner in the Basque forests.

Nowadays, Olentzero seems to be a cross between a symbol of Basque rural life and Father Christmas. He wears traditional Basque clothes (beret and scarf etc. rather than red gown), he’s jolly and chubby, he drinks and smokes a pipe, he sometimes has a white beard, and he brings presents to children. And he’s a coalman – so he has a genuine reason for coming down the chimney!

However, this is a rather sanitised version of the original stories, apparently promulgated during the post-Franco Basque revival in the 70s and 80s. In the original stories, he was sometimes depicted as a rather frightening man of the forests and mountains. This dark side of him is clearly signalled by his occupation – coalman – and even in the lovable modern version, he is sometimes shown with his face covered in coal dust.

In Bilbao, there’s an Olentzero parade on December 23rd, to mark his arrival into the city from the mountains. This is really the Bilbaino equivalent of pantomime, and just about every child in the city comes into the centre of town to see it. The scene on Gran Via was quite amazing: thousands of wide-eyed little children being held on their parents’ shoulders to wave at Olentzero as he went past!

Here's a rather good video of the event from the internet, followed by some of my photos:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3CxrNfInno

There are several different versions of the Olentzero story, but basically he is said to be one of the ‘jentillak’, the giants of the Pyrenees which are at the core of Basque mythology – along with the mountain-men – ‘basajaunak’, the river-maidens – ‘lamiak’, and the mountain goddess Mari (probably no direct relationship to the Christian Mary, by the way). Interestingly, the word ‘jentillak’ has the same origins as the word ‘gentiles’ – meaning pre-Christian. It is now thought by many that the Basques may have been here in the foothills of the Pyrenees since the Stone Age, and the jentillak are said to be the mountain giants who built the dolmens and other ancient structures in the Basque mountains. They eventually disappeared, leaving only Olentzero behind. Olentzero then left the mountains and became a Christian, earning his living as a coalman / charcoal-burner in the Basque forests.

Nowadays, Olentzero seems to be a cross between a symbol of Basque rural life and Father Christmas. He wears traditional Basque clothes (beret and scarf etc. rather than red gown), he’s jolly and chubby, he drinks and smokes a pipe, he sometimes has a white beard, and he brings presents to children. And he’s a coalman – so he has a genuine reason for coming down the chimney!

However, this is a rather sanitised version of the original stories, apparently promulgated during the post-Franco Basque revival in the 70s and 80s. In the original stories, he was sometimes depicted as a rather frightening man of the forests and mountains. This dark side of him is clearly signalled by his occupation – coalman – and even in the lovable modern version, he is sometimes shown with his face covered in coal dust.

In Bilbao, there’s an Olentzero parade on December 23rd, to mark his arrival into the city from the mountains. This is really the Bilbaino equivalent of pantomime, and just about every child in the city comes into the centre of town to see it. The scene on Gran Via was quite amazing: thousands of wide-eyed little children being held on their parents’ shoulders to wave at Olentzero as he went past!

Here's a rather good video of the event from the internet, followed by some of my photos:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3CxrNfInno

Olentzero is accompanied by his wife Mari Domingi, a variation on the ancient Basque goddess figure Mari. (Another variation, Marijaia, is the symbol of the Bilbao summer fiesta).

And there are also the Basajuanes - the mythological wild mountain men who often feature in Basque country dances:

Then on Christmas Eve, people carry effigies of Olentzero around the streets, and sing special Olentzero carols. Children collect sweets and treats on the way.

You can see some rousing performance of Olentzero carols, and some images of Olentzero doing what he does, here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHto3CoDICs

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjRXb_cds0w

and this is a splendid one filmed in a Basque village:

http://vimeo.com/18082024

You can see some rousing performance of Olentzero carols, and some images of Olentzero doing what he does, here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHto3CoDICs

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjRXb_cds0w

and this is a splendid one filmed in a Basque village:

http://vimeo.com/18082024

Dec 24 – Nochebuena

At Christmas, the main meal (usually fish followed by ‘turron’) takes place on Christmas Eve (‘nochebuena’). We had an Anglo-Italian Christmas with Pietro’s Italian boss, his English wife, their children and his Italian sister’s family, in a village a few miles outside Bilbao. We started with English mince pies and Polish poppy-seed cake at the nearby house of another English scientist and his Polish wife, and then moved on to the main meal – delicious ravioli followed by salmon, with yummy Basque Cake (‘Pastel Vasco’) and almond cake afterwards. Here’s the Pastel Vasco, with the very ancient Basque symbol, the ‘Lauburu’ or Basque Cross, on it. (Yes, it is related to the swastika, but never mind that.)

At Christmas, the main meal (usually fish followed by ‘turron’) takes place on Christmas Eve (‘nochebuena’). We had an Anglo-Italian Christmas with Pietro’s Italian boss, his English wife, their children and his Italian sister’s family, in a village a few miles outside Bilbao. We started with English mince pies and Polish poppy-seed cake at the nearby house of another English scientist and his Polish wife, and then moved on to the main meal – delicious ravioli followed by salmon, with yummy Basque Cake (‘Pastel Vasco’) and almond cake afterwards. Here’s the Pastel Vasco, with the very ancient Basque symbol, the ‘Lauburu’ or Basque Cross, on it. (Yes, it is related to the swastika, but never mind that.)

We were joined for Christmas by a very obliging gang of insects who showed great interest in one of our desserts:

3. Dec 31: New Year’s Eve - Nochevieja

Sadly, we won’t be here for New Year, but the tradition is to eat 12 white grapes at midnight, one for each month. Eat them before the twelve chimes are up if you want good luck in the coming year.

4. Jan 6: Dia de los Reyes – Day of the Kings

Again, sadly we won’t be here on January 6th. But this is the biggest celebration of the season. Big parades. People dress up as the three kings. More presents. And no doubt lots of singing, dancing, eating and drinking on the streets….

Sadly, we won’t be here for New Year, but the tradition is to eat 12 white grapes at midnight, one for each month. Eat them before the twelve chimes are up if you want good luck in the coming year.

4. Jan 6: Dia de los Reyes – Day of the Kings

Again, sadly we won’t be here on January 6th. But this is the biggest celebration of the season. Big parades. People dress up as the three kings. More presents. And no doubt lots of singing, dancing, eating and drinking on the streets….

And finally…

Zorionak! Happy New Year! I leave you with a few pictures of Bilbao at Christmas:

Zorionak! Happy New Year! I leave you with a few pictures of Bilbao at Christmas:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed