I seem to have managed to avoid writing about the Guggenheim so far, even though it is the one thing everyone knows about Bilbao. Well, here goes.

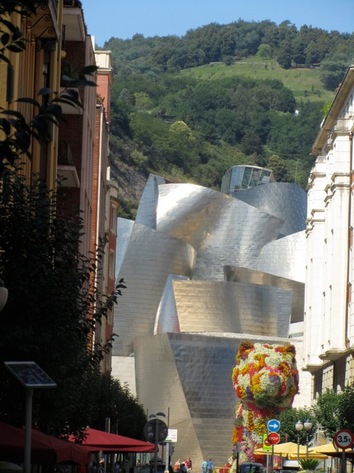

It is an extraordinary building. Built on the old shipyard that dominated the centre of Bilbao until the industrial collapse of the 1980s, Gehry’s structure clearly echoes the ships that were built there, with its metallic skin, its central mast and lookout, its prow and stern, and its mixture of curvaceous and angular shapes. It also seems to float on the river, its moat-like lake connecting with the river water.

The outside is covered in titanium tiles, thin as paper but very strong and rustproof, which glimmer spectacularly in the sunlight, and look incredible against the blue skies which we so often have here.

By the river, in front of the museum, there are two rather wonderful sculptures - Anish Kapoor´s tower of reflecting metal balls, and Louise Bourgeois´ spider, both of which play with light and sky in very rewarding ways.

On the other side of the museum, by the entrance, is Jeff Koons’ absurd ‘Puppy’, covered in flowers, much-loved by the people of Bilbao, (who seem to love dogs even more than the British, judging by the numbers of them around the city.)

Although in some senses the building clearly sticks out like a sore thumb, making a very extravagant statement of difference, the whole ensemble is intended to be linked to the surrounding city by a series of devices – including the moat, the sculptures, the tram-line, the riverside promenade, and the extraordinary bending gateway tower.

The tower is separate from the museum itself but serves as a kind of announcement of the museum´s presence. As you walk from the old town along the river towards the museum (it’s a 25-minute walk from our flat), the first thing you see, from some way off, is the tower; it´s not till you turn the bend in the river that you see the museum itself.

Once you get past the tower, you discover that it is in fact empty apart from a metal scaffold and a staircase that leads up to the bridge across the river.

The bridge was there long before the Guggenheim. It´s quite a dramatic structure in its way – going very high and at an angle over the river, leading up from the 19th century new town into the hills above the city, and offering spectacular and beautiful views over the whole city. But it´s not a beautiful bridge.

The Guggenheim is built around the lower parts of the structure of the bridge, and the bending tower helps to link the bridge to the museum, creating a kind of gateway into both the town and the museum. This effect is heightened by the bold red archway which was also built over the bridge.

From the river you ascend, along the side of the building, up a handsome flight of stairs to the puppy and the museum entrance. This side of the building is made of stone and also has some spectacular features.

Once at the top, you then have to go all the way down again – another handsome flight of stairs – into a kind of well at the bottom where the reception area is.

It´s a beautiful entrance but it is more than a little irritating to be forced to go down all the distance you´ve just come up. In that sense, it´s certainly not a practical building. My mother, who has some difficulties walking, was appalled at the sheer distance she had to walk to get into and around it, the huge number of steps she had to negotiate, and the uncomfortably wide span of all those steps. But – however irritating that undoubtedly must be if you want to get in and see the art inside without exhausting yourself – it does underline the fact that the building is itself the main exhibit, a work of sculptural art in its own right.

The building is perhaps even more extraordinary inside than out. Once you´ve moved away from the ticket sales area, you immediately find yourself in the amazing high atrium, the centre of the museum both vertically and horizontally. You find yourself unable to comprehend how a structure of this complexity could have been built at all. How could the architect have imagined it? How could the builders have been instructed to construct it? What kind of language would have been needed to tell them how to place the materials?

The spaces inside the museum are very fluid, and the experience of moving around inside is unlike any other building I´ve been to. The conventional experience of moving from room to room doesn´t quite apply; the building leads you around itself rather in the manner of an ornamental garden whose pools, rockeries, bridges, grottos and tunnels open out unexpectedly along meandering pathways. It’s marvellous – and yet, again, it rather conflicts with the experience of seeing the art: you´re never quite sure where you are in an exhibition.

There´s a permanent exhibition on the ground floor which consists mainly of Richard Serra´s amazing steel sculptures – the rusting metal and the curving and angular walls again very reminiscent of the ships which used to be made on the very spot. Walking inside and around these structures is disorienting in much the same way as walking around a tilting ship.

The rest of the building is devoted to temporary exhibitions: at any one time, there´s usually an exhibition of some of the Guggenheim´s collection, which is displayed in rotation at its various museums; a major visiting exhibition – recently the big Hockney show which was in London previously, and now a major Claes Oldenburg show; and a smaller exhibition – currently Egon Schiele’s very interesting drawings.

And then there´s a very beautiful bookshop with some of the shapeliest shelves you´ve ever seen, a nice café, and an expensive restaurant which apparently serves some of the best food in the Basque Country made by one of the finest chefs in the region.

There´s no doubt that it´s a remarkable building. ‘But is it a Social Good?’, I hear you ask?

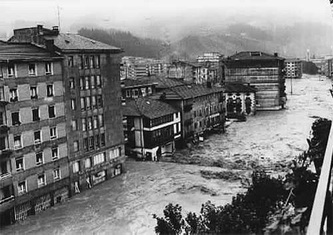

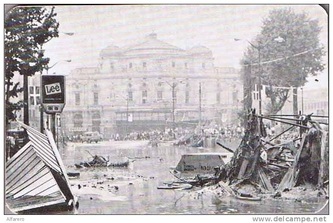

Well, that´s an interesting question. ‘The Guggenheim Effect’ has been much described and much debated since the building materialised in 1997. It is one of the world’s iconic regeneration projects, using art and culture to revive a dying industrial landscape, and now copied in one way or another across the world. On the one hand, it is credited with rescuing the city from its disastrous industrial collapse by signalling its daring, dynamic approach to regeneration to an admiring world – attracting many new businesses, creating many new jobs and leading the way for many other cultural projects, as well as bringing tourists in large numbers to a city which tourists had little reason to visit before. On the other hand, it is criticised as a monstrous capitalist high-art imposition which has little or nothing to do with the real Bilbao or its Basque tradition, doesn’t do anything to foster or even exhibit Basque art, only attracts art-tourists who have no regard for the real culture and traditions of the city and its surrounding coast and countryside, disfigures the environment, and has helped to displace ordinary people from their homes by catalysing a process of gentrification without actually attending to the social and economic needs of ordinary people.

There’s no doubt that the museum has been incredibly successful, as part of a wider regeneration project, in many ways. Everyone agrees that Bilbao has been transformed from a city marked by industrial pollution and decay into a handsome city, and from a place known for terrorist violence into a place of peace (though the latter has as much to do with other political processes as with the transformation of the city). Before the Guggenheim, Bilbao was simply not on the tourist agenda; now it attracts millions each year. Businesses have been attracted to the city, and the unemployment rise (from 3% to 25% between 1975 and 1985) has been reversed (it’s now around 15%, and was lower before the recession).

But there are other sides to the argument. It´s interesting, for instance, that research shows that the majority of tourists who visit Bilbao check in for about 24 hours. They stay in a hotel near the museum, have a meal in one of the tourist-oriented restaurants near the museum, and basically just visit the museum before moving on, without attempting to get to know, or understand the complexity of, Bilbao. The vast majority don´t come anywhere near the atmospheric old town where we live; and we certainly rarely hear languages other than Spanish and Basque being spoken anywhere except close to the museum. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? Not sure…. But you can see lots of reasons – cultural, political and economic – why some might resent or criticise it, especially at a time of austerity and in a city with a complex cultural and political identity.

There’s a strong argument that, despite its rather abstract attempts to link physically with its environment, it´s not a very hospitable building spiritually. It squats self-importantly in the middle of the city; it´s oversized and not very people-friendly; there’s little about it that reflects the very dynamic life of the city around it or attracts anyone other than tourists to it. Whilst there are some successful public spaces around it, there are also some pretty dead spaces too; and the public spaces are really only used by tourists visiting the museum – there´s no other reason to go to them.

Linked to this architectural criticism, there is the controversy surrounding the commodification of art and culture in the service of economic regeneration which many felt the Guggenheim represented. The whole project seemed to treat art as merely capitalist commodity; many local artists and cultural figures objected strongly – embittered also by the channelling of huge amounts of Basque public money into this one flagship project. A major Basque Cultural Centre which had been planned – and which is to this day a huge omission from the cultural life of Bilbao – was jettisoned in favour of the Guggenheim, and many other local and regional arts projects had their funding cut.

So there was a great deal of hostility to the project locally, especially from left-wing Basque nationalists, who saw the whole thing as selling out to the forces of globalising American cultural imperialism and sidelining the real culture and people of Bilbao, as well as their immediate economic and social needs. This investment in the regeneration of inner-city industrial wasteland through glamorous cultural projects designed to attract tourism, business and other capitalist benefits to a city has even been described (disparagingly) as ‘McGuggenisation’ in recognition of the role that the Guggenheim played in developing this model of American corporate-style expansion (Donald McNeill, ‘McGuggenisation? National identity and globalisation in the Basque Country’, Political Geography 19 (2000) 473-494).

The Basque terrorist group ETA certainly didn´t like it when it was built. They hatched a plot to blow it up around the time of its opening. The plot was discovered and prevented, but a policeman was killed in the process.

The politics of the Guggenheim are complex, though, as McNeill explains. Many Basque nationalists objected - but in fact it was Basque nationalists (centre-right ones) who forged the deal that brought the Guggenheim to Bilbao. They saw it not only as a catalyst for regeneration but also as part of a move towards establishing the Basque Country as an independent player in global culture and politics – two fingers up to Madrid, in effect. Because the Spanish constitution devolves power extensively to the autonomous regions that make up the country, the regions are able to make many significant decisions independently of Madrid; this is particularly true of the Basque Country which is not only comparatively wealthy but also, relative to all the other regions of Spain, has a high level of fiscal independence. So the Guggenheim was Bilbao’s way of saying to Spain: ‘look what we can do without you.’

So that´s the Guggenheim. What you probably didn´t know is that there is another superb – and arguably far more culturally integrated – art museum in Bilbao – the Museo de Belles Artes. And that will be the subject of a future post….

Well, that´s an interesting question. ‘The Guggenheim Effect’ has been much described and much debated since the building materialised in 1997. It is one of the world’s iconic regeneration projects, using art and culture to revive a dying industrial landscape, and now copied in one way or another across the world. On the one hand, it is credited with rescuing the city from its disastrous industrial collapse by signalling its daring, dynamic approach to regeneration to an admiring world – attracting many new businesses, creating many new jobs and leading the way for many other cultural projects, as well as bringing tourists in large numbers to a city which tourists had little reason to visit before. On the other hand, it is criticised as a monstrous capitalist high-art imposition which has little or nothing to do with the real Bilbao or its Basque tradition, doesn’t do anything to foster or even exhibit Basque art, only attracts art-tourists who have no regard for the real culture and traditions of the city and its surrounding coast and countryside, disfigures the environment, and has helped to displace ordinary people from their homes by catalysing a process of gentrification without actually attending to the social and economic needs of ordinary people.

There’s no doubt that the museum has been incredibly successful, as part of a wider regeneration project, in many ways. Everyone agrees that Bilbao has been transformed from a city marked by industrial pollution and decay into a handsome city, and from a place known for terrorist violence into a place of peace (though the latter has as much to do with other political processes as with the transformation of the city). Before the Guggenheim, Bilbao was simply not on the tourist agenda; now it attracts millions each year. Businesses have been attracted to the city, and the unemployment rise (from 3% to 25% between 1975 and 1985) has been reversed (it’s now around 15%, and was lower before the recession).

But there are other sides to the argument. It´s interesting, for instance, that research shows that the majority of tourists who visit Bilbao check in for about 24 hours. They stay in a hotel near the museum, have a meal in one of the tourist-oriented restaurants near the museum, and basically just visit the museum before moving on, without attempting to get to know, or understand the complexity of, Bilbao. The vast majority don´t come anywhere near the atmospheric old town where we live; and we certainly rarely hear languages other than Spanish and Basque being spoken anywhere except close to the museum. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? Not sure…. But you can see lots of reasons – cultural, political and economic – why some might resent or criticise it, especially at a time of austerity and in a city with a complex cultural and political identity.

There’s a strong argument that, despite its rather abstract attempts to link physically with its environment, it´s not a very hospitable building spiritually. It squats self-importantly in the middle of the city; it´s oversized and not very people-friendly; there’s little about it that reflects the very dynamic life of the city around it or attracts anyone other than tourists to it. Whilst there are some successful public spaces around it, there are also some pretty dead spaces too; and the public spaces are really only used by tourists visiting the museum – there´s no other reason to go to them.

Linked to this architectural criticism, there is the controversy surrounding the commodification of art and culture in the service of economic regeneration which many felt the Guggenheim represented. The whole project seemed to treat art as merely capitalist commodity; many local artists and cultural figures objected strongly – embittered also by the channelling of huge amounts of Basque public money into this one flagship project. A major Basque Cultural Centre which had been planned – and which is to this day a huge omission from the cultural life of Bilbao – was jettisoned in favour of the Guggenheim, and many other local and regional arts projects had their funding cut.

So there was a great deal of hostility to the project locally, especially from left-wing Basque nationalists, who saw the whole thing as selling out to the forces of globalising American cultural imperialism and sidelining the real culture and people of Bilbao, as well as their immediate economic and social needs. This investment in the regeneration of inner-city industrial wasteland through glamorous cultural projects designed to attract tourism, business and other capitalist benefits to a city has even been described (disparagingly) as ‘McGuggenisation’ in recognition of the role that the Guggenheim played in developing this model of American corporate-style expansion (Donald McNeill, ‘McGuggenisation? National identity and globalisation in the Basque Country’, Political Geography 19 (2000) 473-494).

The Basque terrorist group ETA certainly didn´t like it when it was built. They hatched a plot to blow it up around the time of its opening. The plot was discovered and prevented, but a policeman was killed in the process.

The politics of the Guggenheim are complex, though, as McNeill explains. Many Basque nationalists objected - but in fact it was Basque nationalists (centre-right ones) who forged the deal that brought the Guggenheim to Bilbao. They saw it not only as a catalyst for regeneration but also as part of a move towards establishing the Basque Country as an independent player in global culture and politics – two fingers up to Madrid, in effect. Because the Spanish constitution devolves power extensively to the autonomous regions that make up the country, the regions are able to make many significant decisions independently of Madrid; this is particularly true of the Basque Country which is not only comparatively wealthy but also, relative to all the other regions of Spain, has a high level of fiscal independence. So the Guggenheim was Bilbao’s way of saying to Spain: ‘look what we can do without you.’

So that´s the Guggenheim. What you probably didn´t know is that there is another superb – and arguably far more culturally integrated – art museum in Bilbao – the Museo de Belles Artes. And that will be the subject of a future post….

RSS Feed

RSS Feed