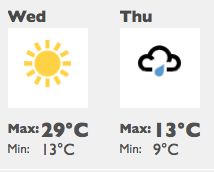

So last weekend – a weekend of glorious sunshine as it turned out – we decided to expand our horizons by going on a jaunt to a city in a different region of Spain! Unbelievably, we have only so far set foot once outside our own region, and that was to go to Barcelona last September. Time for that to change…

So off we popped to Pamplona for the weekend.

I say ‘a different region of Spain´, but actually that may be rather over-stating matters. We were actually still in the Basque Country, but we weren´t in the Basque Region. It’s complicated. Pamplona is in Navarra (‘Nafarroa’ in Basque) which is not in the Basque Autonomous Region (‘Euskadi’ in Basque) where Bilbao is, but is nevertheless still in the Basque Country (‘Euskal Herria’ in Basque).

So off we popped to Pamplona for the weekend.

I say ‘a different region of Spain´, but actually that may be rather over-stating matters. We were actually still in the Basque Country, but we weren´t in the Basque Region. It’s complicated. Pamplona is in Navarra (‘Nafarroa’ in Basque) which is not in the Basque Autonomous Region (‘Euskadi’ in Basque) where Bilbao is, but is nevertheless still in the Basque Country (‘Euskal Herria’ in Basque).

Let me explain:

· The Basque Autonomous Region of Spain (Euskadi) comprises the three provinces of Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Alava (centred on the cities of Bilbao, San Sebastian and Vitoria respectively).

· Navarra is a separate autonomous region, different from, but neighbouring, Euskadi, but nevertheless still a region in the Basque Country (‘Euskal Herria’).

· ‘Euskal Herria’ (´The Basque Country’ - literally ´Basque-speaking Homeland’) is the name given to the wider area – spanning both Spain and France – where the Basques have always been – and continue to be – the dominant population. This area comprises the Basque Autonomous Region of Spain (Euskadi), the three provinces of the French ‘Pays Basque’ … AND the Spanish autonomous region of Navarra, which is NOT part of Euskadi but IS part of Euskal Herria. (Or at least the Northern part of it is – but that´s all a bit controversial.)

· Confusingly, the Basque Autonomous Region, ‘Euskadi’ in Basque, is known as ‘Pais Vasco’ (‘Basque Country’) in Spanish, so that doesn’t really help matters.

· The Basque Autonomous Region of Spain (Euskadi) comprises the three provinces of Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Alava (centred on the cities of Bilbao, San Sebastian and Vitoria respectively).

· Navarra is a separate autonomous region, different from, but neighbouring, Euskadi, but nevertheless still a region in the Basque Country (‘Euskal Herria’).

· ‘Euskal Herria’ (´The Basque Country’ - literally ´Basque-speaking Homeland’) is the name given to the wider area – spanning both Spain and France – where the Basques have always been – and continue to be – the dominant population. This area comprises the Basque Autonomous Region of Spain (Euskadi), the three provinces of the French ‘Pays Basque’ … AND the Spanish autonomous region of Navarra, which is NOT part of Euskadi but IS part of Euskal Herria. (Or at least the Northern part of it is – but that´s all a bit controversial.)

· Confusingly, the Basque Autonomous Region, ‘Euskadi’ in Basque, is known as ‘Pais Vasco’ (‘Basque Country’) in Spanish, so that doesn’t really help matters.

As you might imagine it´s all a bit of a political minefield. I’ll come back to that later.

Anyway, it was a fascinating and very enjoyable weekend – and a very typical weekend in a Basque city, with all the usual elements:

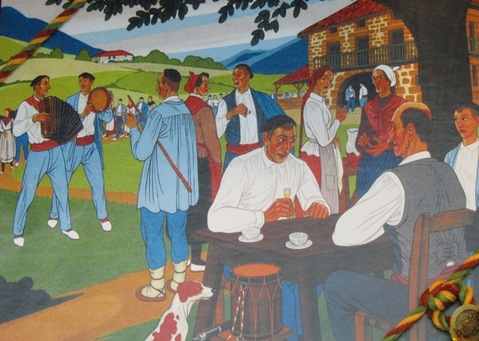

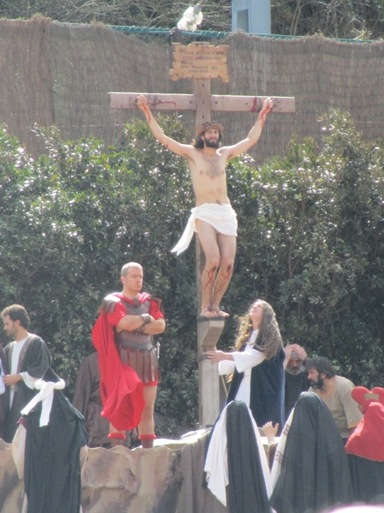

· a fiesta with folk dance and music in the streets

· several political demonstrations

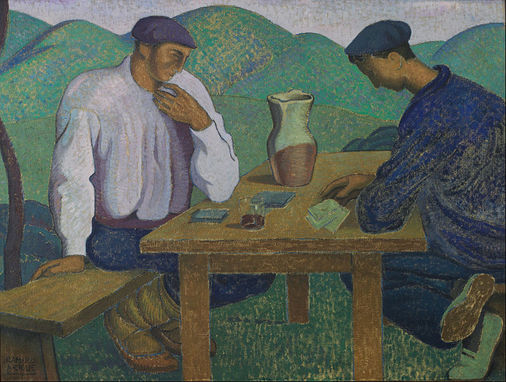

· thousands of people eating, drinking and talking al fresco most of the day and night.

On top of that, Pamplona is a very historic and beautiful city with Lots of Important Sights.

Pamplona´s historical significance – it was a Basque settlement called Iruna before the Romans (still called ‘Iruna’ in Basque), a Roman city (Pompaelo, named after Pompey), and a major religious and military centre throughout the middle ages from the fall of Rome onwards – is a result of its natural defensive position at the end of the main route from France to Spain through the western Pyrenees, the valley which has the historic Pyrenean border town of Roncesvalles at the other end.

Pamplona-Iruna sits atop a massive cliff which looks out over the valley through which invaders would come from France. The existence of this route also, by the way, explains why the Basques in the more northerly provinces of Euskadi were generally left alone by invaders: no-one was interested in occupying the inhospitable Basque mountain land: they just headed south along the pass from Roncesvalles to Pamplona. Consequently Pamplona is often spoken of as ´the Gateway to Spain´.

For this reason, too, Pamplona became famous as one of the major centres of the Pilgrimage of Saint James, since it is on the main pilgrimage route from France:

Anyway, it was a fascinating and very enjoyable weekend – and a very typical weekend in a Basque city, with all the usual elements:

· a fiesta with folk dance and music in the streets

· several political demonstrations

· thousands of people eating, drinking and talking al fresco most of the day and night.

On top of that, Pamplona is a very historic and beautiful city with Lots of Important Sights.

Pamplona´s historical significance – it was a Basque settlement called Iruna before the Romans (still called ‘Iruna’ in Basque), a Roman city (Pompaelo, named after Pompey), and a major religious and military centre throughout the middle ages from the fall of Rome onwards – is a result of its natural defensive position at the end of the main route from France to Spain through the western Pyrenees, the valley which has the historic Pyrenean border town of Roncesvalles at the other end.

Pamplona-Iruna sits atop a massive cliff which looks out over the valley through which invaders would come from France. The existence of this route also, by the way, explains why the Basques in the more northerly provinces of Euskadi were generally left alone by invaders: no-one was interested in occupying the inhospitable Basque mountain land: they just headed south along the pass from Roncesvalles to Pamplona. Consequently Pamplona is often spoken of as ´the Gateway to Spain´.

For this reason, too, Pamplona became famous as one of the major centres of the Pilgrimage of Saint James, since it is on the main pilgrimage route from France:

Imagine ambling wearily along the pretty meadows by the river heading into the city having spent days crossing the Pyrenees. As you approach the old bridge across the river…

… you see the massive fortified cliff looming in the distance:

Once over the bridge, you see the spectacular view of Pamplona Cathedral hanging Durham-like over the cliff edge:

You make your way into the city through the Portal di Francia:

… and through the picturesque streets…

… up to the Gothic cathedral (which unfortunately now has a rather overbearing Baroque front).

(Of course, if you´re doing this in medieval times, you´re probably also extremely poor, hungry, smelly and ill, and your subjectivity has been exploited mercilessly by church and state, but let’s not go there….).

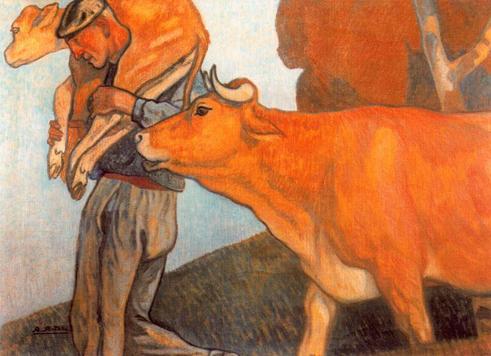

In town, you would probably also want to pay tribute to San Fermin, the patron saint of Pamplona who gives his name to the Sanfermines fiesta each July, famous for the lunatic tradition of the ‘Encierro’, the ‘running of the bulls’ through the streets of the city.

San Fermin was a pupil of San Saturninus (also known as San Cernin) who was martyred by being dragged around Toulouse by a bull. Somehow the names and lives of San Cernin and San Fermin got a bit transposed over the years, and so San Fermin came to be associated with running bulls – and that’s how the Encierro came about.

Here is a picture of Pietro running with the bulls:

In town, you would probably also want to pay tribute to San Fermin, the patron saint of Pamplona who gives his name to the Sanfermines fiesta each July, famous for the lunatic tradition of the ‘Encierro’, the ‘running of the bulls’ through the streets of the city.

San Fermin was a pupil of San Saturninus (also known as San Cernin) who was martyred by being dragged around Toulouse by a bull. Somehow the names and lives of San Cernin and San Fermin got a bit transposed over the years, and so San Fermin came to be associated with running bulls – and that’s how the Encierro came about.

Here is a picture of Pietro running with the bulls:

There’s plenty of bull-running paraphernalia around town…

… and there’s one of the biggest bullrings in Spain:

And of course you can hang out at bullfight-lover Hemingway’s favourite café, Café Iruna:

You can also visit the Romanesque/Gothic church of San Saturnino…

… and the shrine of San Fermin at the Romanesque/Gothic church of Saint Nicolas:

We even came across the entrants to the annual competition for the poster for the San Fermin fiesta, some of which we thought were rather good:

Elsewhere, there is plenty of evidence of Pamplona’s military role. The old city is surrounded by possibly the most extensive ramparts and fortifications in Europe, dating from medieval times until the early 18th century. Most impressive is the 17th century ‘Ciudadela’ which has now become a huge and beautiful green park around the edge of the old city:

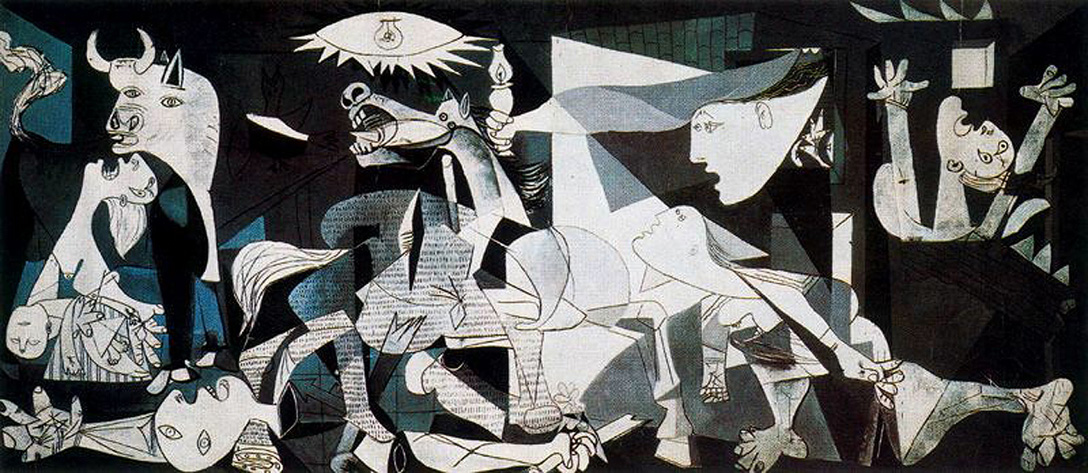

Politics was much in evidence during the weekend, as it often is in the Basque Country. There was a big anti-monarchy demonstration (there was also a big one in Madrid) campaigning for a ‘Third Republic’. (The last one, the Second Republic, was in the years before Franco and the Spanish Civil War, and with the popularity of the royal family having declined pretty severely in the last year or two after the economic crisis and a series of scandals, republicanism is becoming popular again). Anyway, it was all very lively and the distinctive red, yellow and purple flags of the campaign looked very jolly in the streets:

There was also a smaller Basque nationalist demonstration, and plenty of Basque nationalist posters around. As suggested earlier, Navarra is a bit of a flashpoint for Basque nationalism, sometimes described as ‘the Basque Ulster’. This is partly because Navarra is divided between the Basque North and the non-Basque South, which causes political tensions, with Pamplona sitting between the two areas in the centre. But it’s also because, despite its Basque majority, Navarra has always voted against becoming part of a united Basque region, which is why it is not part of Euskadi – so it also represents conflict between Basques, with hard-line Basque nationalists wanting to see Navarra re-united with Euskadi (and indeed with the French Pays Basque too).

Why do many in Navarra not want to be part of Euskadi? Well, the politics and history of it all are phenomenally complicated, but one of the key factors seems to be to that Navarra has traditionally been one of the most politically right-wing, socially conservative and religiously ultra-Catholic parts of Spain, and this has set it against its slightly more liberal neighbours in industrialised Euskadi at several points in modern history – particularly during the 19th century Carlist Wars, during the Spanish Civil War, and at the time of the re-establishment of democracy after Franco’s death, where Basques of the two regions found themselves fighting on different sides. The fact that the Navarrese supported Franco (thinking that this would give them the best chance of maintaining their autonomy) certainly didn’t help relationships between Euskadi and Navarra.

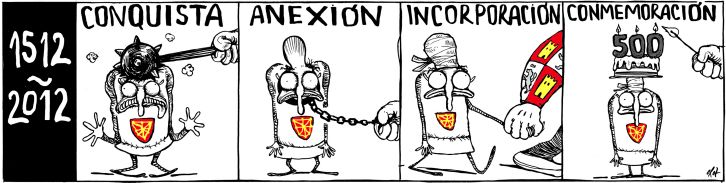

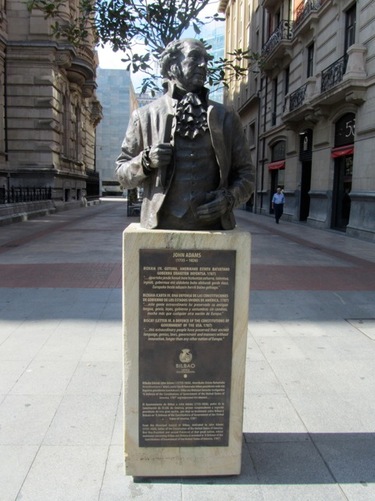

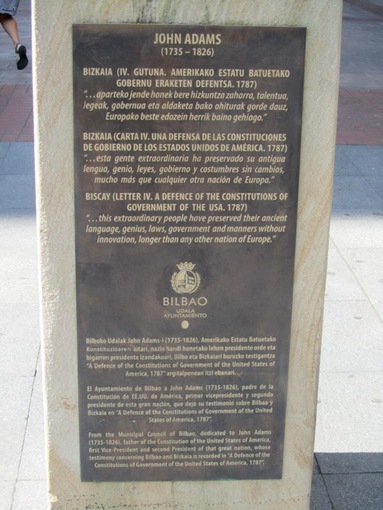

Last year, 2012, was a bit of a milestone in this long-running debate, as it was the 500th anniversary of the conquest of the Kingdom of Navarra by Spain in 1512. Again, the history is very complicated, but this is seen as marking the end of a period which had represented the only time in history when all the Basque regions (including the French ones) had been united in an independent state and allowed to maintain their ‘fueros’ (see previous post on Gernika for explanation of what they are) independently of Spain. 1512 is therefore a date which has a great deal of resonance for the Basques, and it’s often used in Basque nationalist protest:

Last year, 2012, was a bit of a milestone in this long-running debate, as it was the 500th anniversary of the conquest of the Kingdom of Navarra by Spain in 1512. Again, the history is very complicated, but this is seen as marking the end of a period which had represented the only time in history when all the Basque regions (including the French ones) had been united in an independent state and allowed to maintain their ‘fueros’ (see previous post on Gernika for explanation of what they are) independently of Spain. 1512 is therefore a date which has a great deal of resonance for the Basques, and it’s often used in Basque nationalist protest:

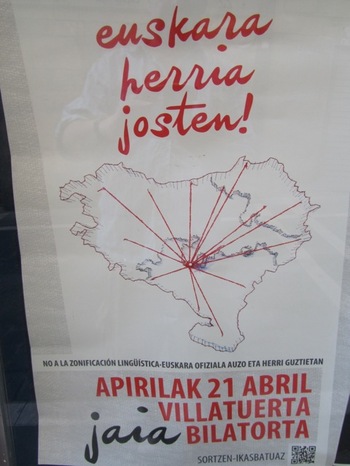

One current manifestation of the cultural argy-bargy in Navarra is the debate about official languages. In Euskadi, it’s relatively straightforward: the official languages are Basque and Spanish throughout. But in Navarra it’s more complicated. So we saw this poster….

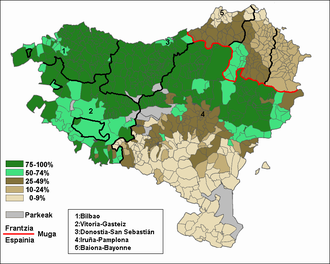

… which is an anti-zonification poster, arguing that Basque should be an official language throughout the whole of Navarra, not just in the Basque zone in the Basque majority Northern area. Interestingly, only about 20% of Navarrese actually speak Basque – but the importance of Basque-speaking zones is that they force the schools to teach Basque to all students, as in Euskadi, so they’re a significant vehicle for national linguistic revival. This mapshows the concentrations of Basque speaking in the Basque Country, displaying the division in Navarra quite clearly:

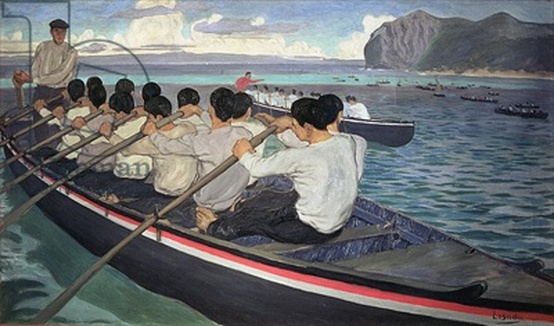

Less controversially, the Basque folk revival is clearly going strong, and there was lots of Basque country dancing going on in the streets…

… including an appearance by the wonderful ‘Joaldunaks’ from the Basque mountains, who not only wear sheepskins and cowbells but also the most fantastic hats:

As for the ultra-Catholic tendencies of Pamplona – well, Pamplona is one of the main centres of the powerful and disturbing Opus Dei movement, and a byword for conservative Catholicism. (In the Guardian yesterday, by coincidence, there was a report that a Spanish revolutionary anarchist group called ‘The Anticlerical Pro Sex Toys Group’ (!!) have been sending explosive packages containing vibrators to the Archbishop of Pamplona…)

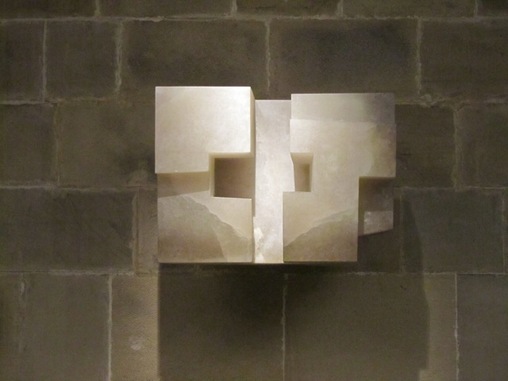

The Opus Dei influence was evident to us in the extraordinary permanent exhibition which has just opened in the cloisters of the Cathedral. Called ‘Occidens’, it purports to tell the story of Western civilisation through the buildings and artefacts of the cathedral precincts.

The Opus Dei influence was evident to us in the extraordinary permanent exhibition which has just opened in the cloisters of the Cathedral. Called ‘Occidens’, it purports to tell the story of Western civilisation through the buildings and artefacts of the cathedral precincts.

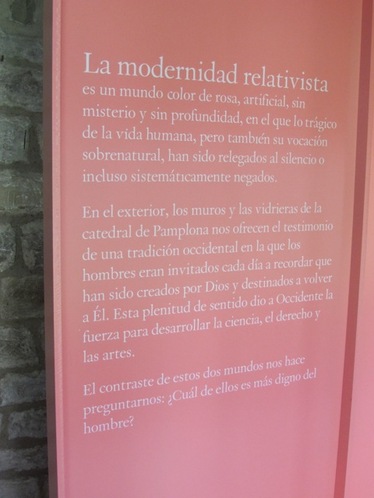

Beautifully designed, with state-of-the-art audio-visuals, lighting, display and graphic design, the whole thing was an outrageous and extremely expensive piece of propaganda for ultra-conservative Catholicism, which essentially argued that without Catholicism there would be no western civilisation. Everything from Democracy to Human Rights, via the Enlightenment, had apparently been encouraged and embraced, if not invented, by the Catholic Church. The final message of the exhibition was that all those achievements are now threatened by modern society, and the church is engaged in a’ fourth crusade’ against the greatest evil of modern society, relativism - depicted bizarrely as "an artificial pink-coloured world without mystery or depth" and represented by a pink plastic shed which we were invited to compare with the splendours of the cathedral...

We ended up angry - not least that we had paid 5 euros each in entrance fees to help finance this appalling nonsense.

To finish on a happier note, we had a lovely stroll around the meadows by the river, where there was an old medieval and 19th century mill which has been converted into a beautiful café overhanging the river, with a wonderful little footbridge across the river, and a spectacular lift to take you up the cliff to the old city above:

To finish on a happier note, we had a lovely stroll around the meadows by the river, where there was an old medieval and 19th century mill which has been converted into a beautiful café overhanging the river, with a wonderful little footbridge across the river, and a spectacular lift to take you up the cliff to the old city above:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed