So off we popped to Pamplona for the weekend.

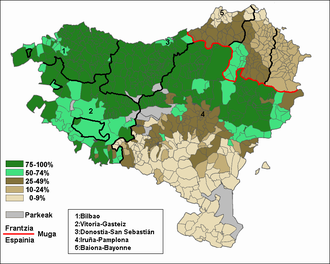

I say ‘a different region of Spain´, but actually that may be rather over-stating matters. We were actually still in the Basque Country, but we weren´t in the Basque Region. It’s complicated. Pamplona is in Navarra (‘Nafarroa’ in Basque) which is not in the Basque Autonomous Region (‘Euskadi’ in Basque) where Bilbao is, but is nevertheless still in the Basque Country (‘Euskal Herria’ in Basque).

· The Basque Autonomous Region of Spain (Euskadi) comprises the three provinces of Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Alava (centred on the cities of Bilbao, San Sebastian and Vitoria respectively).

· Navarra is a separate autonomous region, different from, but neighbouring, Euskadi, but nevertheless still a region in the Basque Country (‘Euskal Herria’).

· ‘Euskal Herria’ (´The Basque Country’ - literally ´Basque-speaking Homeland’) is the name given to the wider area – spanning both Spain and France – where the Basques have always been – and continue to be – the dominant population. This area comprises the Basque Autonomous Region of Spain (Euskadi), the three provinces of the French ‘Pays Basque’ … AND the Spanish autonomous region of Navarra, which is NOT part of Euskadi but IS part of Euskal Herria. (Or at least the Northern part of it is – but that´s all a bit controversial.)

· Confusingly, the Basque Autonomous Region, ‘Euskadi’ in Basque, is known as ‘Pais Vasco’ (‘Basque Country’) in Spanish, so that doesn’t really help matters.

Anyway, it was a fascinating and very enjoyable weekend – and a very typical weekend in a Basque city, with all the usual elements:

· a fiesta with folk dance and music in the streets

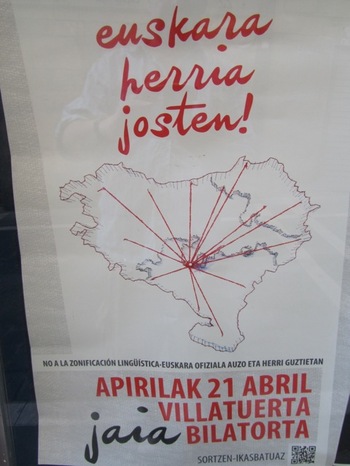

· several political demonstrations

· thousands of people eating, drinking and talking al fresco most of the day and night.

On top of that, Pamplona is a very historic and beautiful city with Lots of Important Sights.

Pamplona´s historical significance – it was a Basque settlement called Iruna before the Romans (still called ‘Iruna’ in Basque), a Roman city (Pompaelo, named after Pompey), and a major religious and military centre throughout the middle ages from the fall of Rome onwards – is a result of its natural defensive position at the end of the main route from France to Spain through the western Pyrenees, the valley which has the historic Pyrenean border town of Roncesvalles at the other end.

Pamplona-Iruna sits atop a massive cliff which looks out over the valley through which invaders would come from France. The existence of this route also, by the way, explains why the Basques in the more northerly provinces of Euskadi were generally left alone by invaders: no-one was interested in occupying the inhospitable Basque mountain land: they just headed south along the pass from Roncesvalles to Pamplona. Consequently Pamplona is often spoken of as ´the Gateway to Spain´.

For this reason, too, Pamplona became famous as one of the major centres of the Pilgrimage of Saint James, since it is on the main pilgrimage route from France:

In town, you would probably also want to pay tribute to San Fermin, the patron saint of Pamplona who gives his name to the Sanfermines fiesta each July, famous for the lunatic tradition of the ‘Encierro’, the ‘running of the bulls’ through the streets of the city.

San Fermin was a pupil of San Saturninus (also known as San Cernin) who was martyred by being dragged around Toulouse by a bull. Somehow the names and lives of San Cernin and San Fermin got a bit transposed over the years, and so San Fermin came to be associated with running bulls – and that’s how the Encierro came about.

Here is a picture of Pietro running with the bulls:

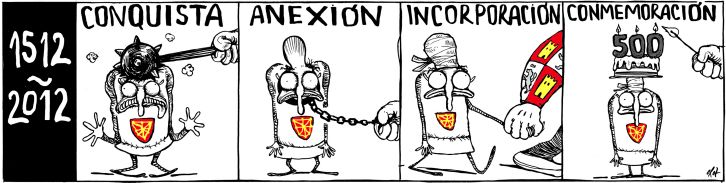

Last year, 2012, was a bit of a milestone in this long-running debate, as it was the 500th anniversary of the conquest of the Kingdom of Navarra by Spain in 1512. Again, the history is very complicated, but this is seen as marking the end of a period which had represented the only time in history when all the Basque regions (including the French ones) had been united in an independent state and allowed to maintain their ‘fueros’ (see previous post on Gernika for explanation of what they are) independently of Spain. 1512 is therefore a date which has a great deal of resonance for the Basques, and it’s often used in Basque nationalist protest:

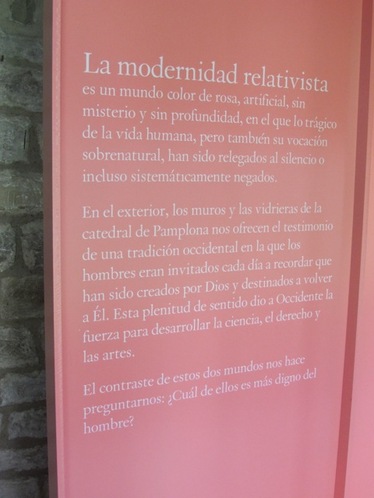

The Opus Dei influence was evident to us in the extraordinary permanent exhibition which has just opened in the cloisters of the Cathedral. Called ‘Occidens’, it purports to tell the story of Western civilisation through the buildings and artefacts of the cathedral precincts.

To finish on a happier note, we had a lovely stroll around the meadows by the river, where there was an old medieval and 19th century mill which has been converted into a beautiful café overhanging the river, with a wonderful little footbridge across the river, and a spectacular lift to take you up the cliff to the old city above:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed