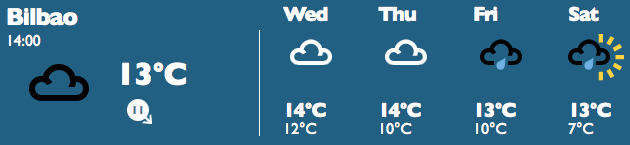

Whats going on? It has been warmer in England than here this week! We had some glorious weather a couple of weeks ago, but apart from that the last mo it's been dismal.... The average maximum in May is supposed to be 20 degrees

|

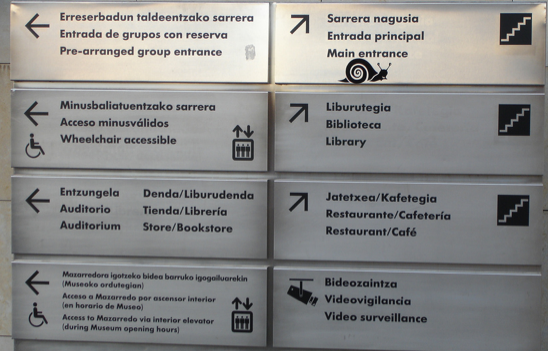

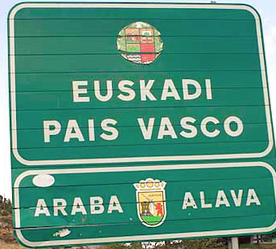

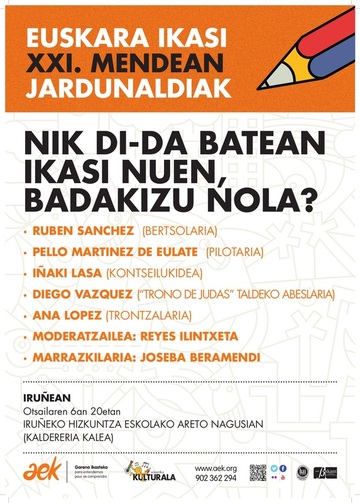

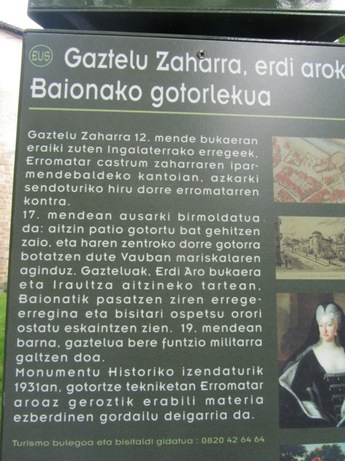

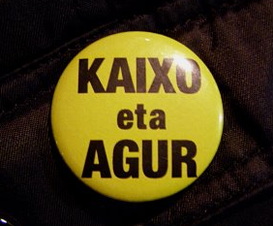

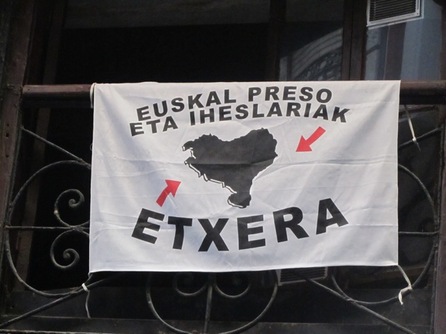

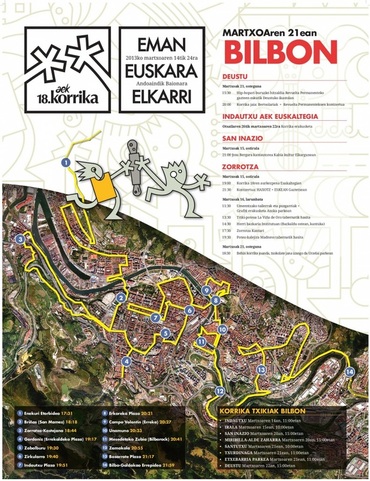

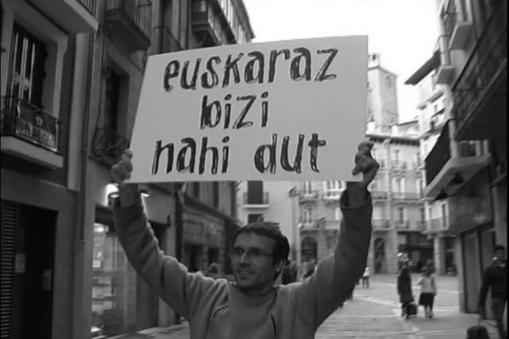

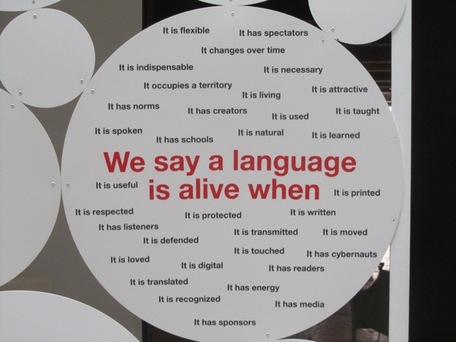

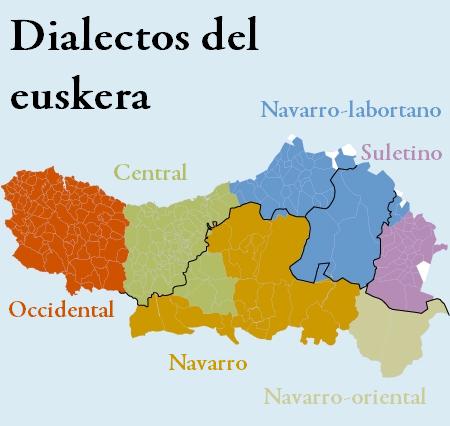

Euskaraz bizi nahi dut = we want to live life in Basque Euskara, the Basque language, is completely unrelated to any other language, a language isolate, the most ancient in Europe, the last remaining vestige of the languages spoken in Europe before the Indo-Europeans came. It is one of the most fascinating things about the Basque country, and perhaps the most powerful focus for Basque nationalism (which I’ll write about in more detail in a later post). As with the Celtic languages in Wales, Ireland and parts of Scotland, Euskara is compulsory these days for all young people in school, so, whether native Basque or immigrant, you will learn Euskara. There are three types of school, and you can choose to go to any of them: Basque-speaking, Spanish-speaking or mixed Basque and Spanish. Whichever you go to, you’ll have to learn both Basque and Spanish. (Basque-speaking schools are called ‘ikastolak’, and the first one was opened in 1914.) Just as in Wales, Ireland and parts of Scotland, a great deal of text here, including all official government text, comes in two languages (Spanish and Euskara). Here are some trilingual signs at the Guggenheim: The big cities have two names, a Spanish one and a Basque one (Bilbao-Bilbo, Vitoria-Gasteiz, San Sebastian-Donostia), as does the entire region (Pais Vasco-Euskadi). There are of course newspapers and tv and radio channels in both Basque and Spanish. The main Basque tv company, EITB, for instance, has one Basque tv channel and one Spanish. It´s quite common, too, to come across texts, unofficial ones – such as political or communal posters, leaflets, etc. – written all in Euskara, leaving non-Euskara speakers completely clueless. You don’t really have a hope with Euskara, as it is completely unrelated to any other language. The extent of Euskara use differs across the Basque country. The heartlands of the Basque language (and of Basque nationalism) are in the mountainous areas in the centre, and along the coast between Bilbao and San Sebastian - but in fact pretty much anywhere outside Bilbao and San Sebastian you are likely to hear a great deal of Basque spoken – and the smaller and more remote the community the more likely that is. (Remember too that Euskara is spoken in the French Pays Basque, though less than in Spanish Basque Country). Here in Bilbao, you don’t hear much Euskara. There are two main reasons why many people don’t speak Euskara in the bigger cities. One is the suppression of the language (and Catalan too in Barcelona) during Franco´s dictatorship, from the 1930s to the 1970s, especially in the cities. As a consequence of this, a whole generation of older people don´t speak Euskara (although many have learnt it since Franco’s demise). In many places, you´re more likely to hear young people, growing up during the 80s and after, speaking it, as they’re the ones who learnt it at school. The other reason is to do with immigration to Bilbao (and other cities, but mainly Bilbao) from other non-Euskara-speaking parts of Spain. Between 1950 and 1970 there was a major industrial boom in the Basque Country. Thousands of people came here, many from the poorer regions in the south of Spain, to find work. The population of the three big cities, and some of the smaller ones too, doubled in those twenty years – and of course this influx of people had no idea about Euskara. But even so, some of them and their children have learnt or are learning Euskara. (This huge influx of workers also explains, by the way, why there is so much horrendous 60s and 70s domestic and commercial building throughout the Basque Country!) Here in central Bilbao you rarely hear Spanish spoken in the streets or shops, though you are more likely to hear it here in the Casco Viejo (old town) or in older parts of the grittier suburbs such as Portugalete, than in the newer or posher parts of Bilbao. (In general, throughout Euskadi, the old towns are slightly grittier areas where left-wing nationalism is likely to thrive and Euskara is more likely to be spoken). We certainly haven’t had to learn any Euskara to get by here – except for two words/phrases which are universally used: ‘agur’ (pronounced ‘agoor’) which means ‘goodbye’ (no one says ‘adios’ except to complete foreigners….), and ‘eskerrik asko,’ which means ‘thank you’ (again ‘gracias’ is mostly used to and by foreigners.) (For some reason, the Euskara for 'hello' ('kaixo') is not used much - people tend to say 'hola' in Spanish, or another Basque word 'aupa' which means something like 'hi' or cheers.) On the other hand, we have picked up a certain amount. ‘K’, ‘x’ and ‘z’ are very common consonants. The unusual consonant cluster is ‘tx’ which is pronounced ‘ch’ as in ‘church’. We pick things up by seeing the Basque equivalents of Spanish words, for instance ‘jatetxea’ for ‘restaurante’. We learn too from learning about Basque culture – for instance we know about ‘bertsolariak’ (improvised verse chanters), ‘txistulariak’ (players of the Basque flute, the ‘txistu’) and various other elements of Basque folk culture. We know that the ‘txistu’ is the flute, the ‘txistulari’ is the player, and that ‘txistulariak’ is the plural of ‘txistulari’, and that the ending ‘-ak’ signifies a plural noun. We know that the word ‘eta’ means ‘and’ (not to be confused with the terrorist group ETA…). We know that ‘ongi etorri’ means ‘welcome’, ‘bai’ means ‘yes’ and ‘ez’ means’ no’. We know that the suffix ‘tegia’ indicates a place where things are made or sold, e.g. a ‘sagardotegia’, a cider (‘sagardo’) house. We know the word ‘etxea’, one of the most important concepts in Basque culture, which means ‘home’, and ‘herria’ which means ‘country’, and that these words can be adjusted to ‘etxera’ and ‘herrira’ to signify movement towards home or the homeland. And so on. (By the way 'etxera' is the slogan of the political movement to have Basque prisoners returned to the Basque country, which I'll write more about later - see picture below.) There’s a great deal of enthusiasm throughout the region for the language, just as there is in parts of Wales, Scotland and Ireland for Welsh and Gaelic. Bilbao still conducts most of its business in Spanish, but even here there is widespread enthusiasm for Euskara, even on the part of those who don’t speak it. Throughout the Basque Country, too, there is a huge movement towards learning Euskara. There are branches of AEK (Alfabetatze Euskalduntze Koordinakundea) all over the place (one of the main ones in Bilbao is on our street) which specialise in running evening classes for people to learn the language, and many people of all ages attend these after work. They also organize events throughout the year throughout the Basque Country designed to promote Euskara, such as bertsolari events (improvised verse chanting – see previous post) and Basque folk song events. There are also two big ‘national’ Euskara-focused events: the ‘Korrika’ and the Basque Language Day. The Korrika is an extraordinary relay race covering hundreds of miles which links most towns in the 'Euskal Herria' – in both France and Spain. Many thousands of people take part in this massive event which symbolically links all the Basque-speaking lands. The slogan this year was 'Eman euskara elkarri' ('Give Basque to one another'). The other event, International Basque Language Day (Euskararen Eguna, December 3rd) sees celebrations happening in cities, towns and villages throughout Euskal Herria. This annual celebration was initiated in 1948 whilst the language was still banned in Euskadi, and celebrated by Basques outside the Basque Country until the language was once again allowed after Franco. The slogan of the day is 'Euskaraz bizi nahi dut' - 'we want to live life in Basque'. Each year, towns around the Basque country make communal 'lipdub' and 'flashmob' videos to celebrate the day which give a sense of the amazing community cohesion and strength of feeling for the language. Massive numbers of people turn out to sing and dance along to a rousing Basque pop anthem recorded for the occasion, Here are some rousing examples: http://vimeo.com/55845328 http://vimeo.com/11260312 http://vimeo.com/43803415 There´s also a Basque Language Centre ('Euskararen Etxea') in Bilbao, a kind of museum where anyone can go to find out all about the language. We haven't yet been but intend to before we leave. And recently there's been a beautifully designed exhibition in San Sebastian about the language called 'badu, bada' (meaning 'it is, it has'): The nerve centre of the various Euskara revivals of the last century, and the current huge growth in the language, is the Basque Language Academy (Euskaltzaindia), created in 1918 in Bilbao, which was responsible in the 1970s for ‘creating’ a viable standard Basque language (‘Batua’) from the several (around 7 or 8) very different geographical dialects of the language that existed, and remains responsible for overseeing the language. (Until the 16th century, Euskara was largely an orally transmitted language. A number of very different dialects developed in different parts of Euskal Herria (so much so that people on one side can’t easily understand people on the other). It wasn’t until the suppression of the language by Franco threatened it with extinction that a standard language was agreed on.) Finally, to give you a further taste of everyday Basque language things, here are some typical personal names.... First names: Male: AITOR, GORKA, INAKI; Female: AMAIA, EDER, IRATI (NB There are many more...) Surnames: Etxebarria, Zubiondo, Bidarte, Ibarra, Gorrotxategi, Extxegoien, Urdangarin, Goikoetxea... etc. ... some typical Basque place names (these are all suburbs of Bilbao)... ... and a couple of local tavern names, written in the classic Basque font, which is derived from ancient inscriptions on stones in the Basque Country: That's all for now! ESKERRIK ASKO and ..... AGUR!

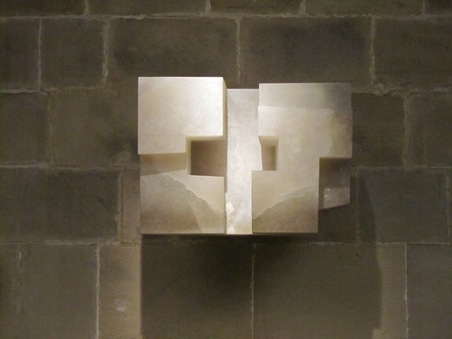

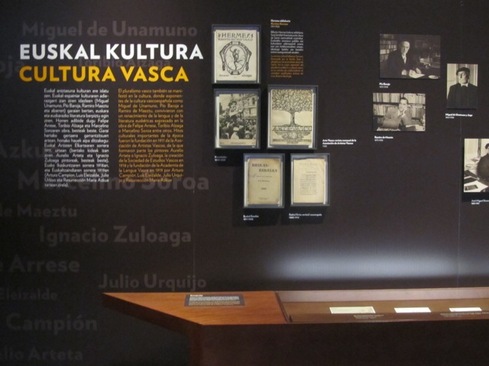

There’s not a lot of glamour in the Basque Country. It’s pretty down-to-earth. But if any part of Euskadi can be described as glamorous then it must be San Sebastian (‘Donostia’ in Basque), 60 miles or so along the coast from Bilbao towards France. It’s where the international film and jazz festivals happen in the summer; it’s where the Spanish royal family used to come for seaside holidays; it’s often said by chefs and other gastronomes that the food in San Sebastian is the best in the world; it’s generally regarded as one of the most upmarket of Spanish seaside resorts. We’ve been here three times now, on separate day trips. There’s no doubt it’s a lovely place, though even the generally pleasing sea front is not immune from some of the truly awful high-rise developments that blighted much of the Basque Country in the 70s and 80s. Perhaps it’s more true of San Sebastian than most other places that it really needs a sunny day to look its best. The Parte Vieja (old town) is relatively down-to-earth, a delightful grid of little streets (often packed with people eating and drinking) lined by hundreds of bars and restaurants: There are some fine old churches… … inside one of which is Chillida’s beautiful marble cross: There’s a handsome arcaded square, with chunky numbers painted above each balcony from the times when the square was used as a bullfighting arena: There’s an old market complex, La Bretxa: And there’s the old harbour overlooked by the splendid town hall: On one side of the old town is the beautiful shell-shaped bay, La Concha, with hills at either end forming a natural harbour entrance: It’s a great hour-long walk from one end of the bay to the other, starting with Oteiza’s ‘Construccion Vacia’ (Empty Construction)... and culminating in Chillida’s ‘El Peine del Vento’ (The Comb of the Wind)... with two other Chillida sculptures along the way - a cross-shaped homage to Fleming... and a knot-like twisted metal post which imitates the beautiful striations of the nearby rocks: On the other side of the old town is the river, with its distinctive bridge: Where the river meets the sea there are often spectacular displays of crashing foam against the rocky shore: Over the river is the district of Gros, with its splendid new concert, exhibition and conference centre, The Cube, on the beach: And behind the old town is a rather grand nineteenth century ‘ensanche’ (new town) stretching up the river, with posh cafes and hotels, handsome shopping streets and a fine neo-Gothic cathedral: As for the food – well there’s an extraordinary concentration of Michelin-starred restaurants here, but it’s as much the quality of ordinary food that makes people rave about San Sebastian. As in Bilbao, food is a source of huge local pride; unlike Bilbao, tourists come to San Sebastian specifically for the food. But the bars and restaurants are just as full all year with local people as they are with tourists in the summer. We’ve only scratched the surface, but it’s clear that the ‘pintxo’ culture here is even more amazing than in Bilbao, with hundreds of bars heaving with wonderful little creations. Without a doubt our favourite pintxo experiences were in the wonderful little Cuchara de San Telmo (The Spoon of San Telmo), a tiny bar behind the San Telmo Museum in the Parte Vieja, overflowing with people trying to get a taste of the superb little ‘pintxos calientes’ - little dishes of utterly delicious food made in the tiny kitchen: Finally, one of the very best things about San Sebastian is the superb San Telmo museum of Basque art and culture, built in the old San Telmo convent and redesigned to the highest standards of museum design just a few years ago. It’s stunning – the building as well as the displays and graphic/audio-visual design.

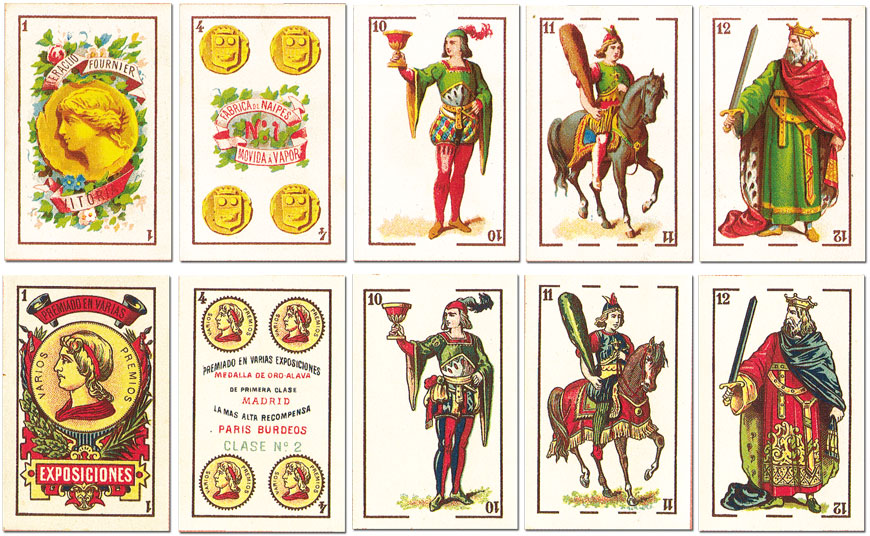

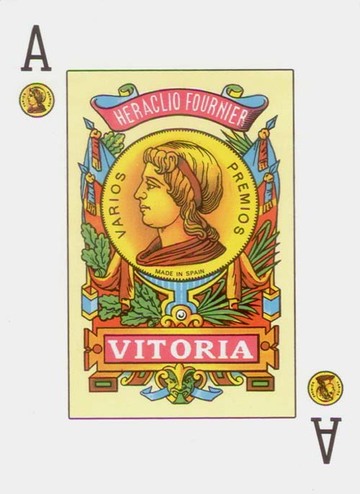

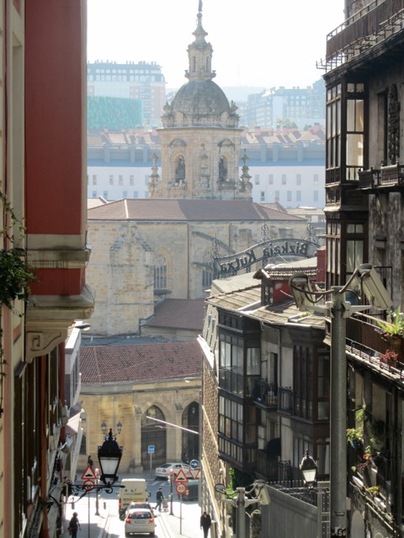

I think most people in Britain have never heard of Vitoria. I certainly hadn´t. Which is a shame, because it´s a nice city – a place that was very important in medieval times but went into a bit of a decline for centuries, didn´t grow much beyond its medieval bounds, and is now full of picturesque and often rather faded medieval corners. Vitoria (‘Gasteiz’ in Basque) is in the province of Araba (‘Alava’ in Basque), the southern (non-coastal) one of the three provinces of Euskadi. Alava is the most rural, least populated and least industrialised of the three provinces, and the one-hour journey south from Bilbao is beautiful, through many unspoilt valleys with wonderful mountain views. Vitoria’s decline was halted in the 70s and 80s, after Franco´s demise, by significant industrial growth and the building of substantial new suburbs – and by the decision to make the city the capital of Euskadi rather than Bilbao or San Sebastian. The modest parliament building is here in Vitoria, and it´s where the President (the ‘Lehendakari’) lives. Tourists do come here, but not that many. You can see why Vitoria might be more appropriate as the capital than the other two cities. Its old town is certainly the most interesting of the three, and it has a genteel hill-town charm that the others don´t really have. The entrance to the old town is the beautiful square of the White Virgin (Plaza di Virgen Blanca), lined with cafes below classic northern-style ‘miradors’ (enclosed balconies), and with a huge memorial to the Battle of Vitoria in the middle…. At the tapered end, steps go up the hill to the church of the White Virgin and a variety of other medieval buildings: Behind this is the Almendra (‘the Almond’), the almond-shaped old town, a lovely network of old streets, many lined by the inevitable huge numbers of bars. These streets are packed with people drinking and eating pintxos each afternoon and evening. At the heart of the old town is the cathedral, a fine Gothic building (replacing a previous Romanesque one) perched on the edge of a cliff in a highly defensive position. The cathedral, which had got into a bit of a state thanks to neglect and the gradual subsidence of the medieval foundations down the hill, has been under restoration for over a decade, a huge project which has involved building massive new foundations to stabilise the whole thing. The restoration team give regular tours of the building: Next to the cathedral are some fine medieval buildings: At the edge of the old town, there’s the usual 18th century arcaded square (Plaza Mayor) … and a variety of pretty 18th and 19th century buildings… as well as the modern art and fine arts museums mentioned in a previous post. It’s also one of the greenest cities in Spain, with lots of parks and an Edwardian garden city. In 2012 it was the Green Capital of Europe. One of the old palaces in the old town has been turned into a great museum complex, comprising a superbly designed history and archaeology museum… … and a fascinating playing card museum. I know it sounds unlikely, but it really is an amazing collection of cards from all over the world, many incredibly beautiful and interesting, going back to medieval times. It’s here because all of Spain’s playing cards are and always have been made here by the firm Fournier. We bought a pack of Fournier cards and had a go at playing the Basque card game ‘Mus’, popular all over Spain:

There´s not a lot left of medieval Bilbao apart from the street plan of the atmospheric old town. The only remnants are the late Gothic churches. Although some look great on the outside but have been liberally Baroque-ified inside, most still have their medieval interiors relatively unspoilt. Five churches in particular, all lining the northern branch (‘Camino del Norte’) of the Santiago de Compostella pilgrimage route, which goes through Bilbao, are worthy of note. Pilgrims on their way to Santiago would first come to Nostra Senora di Begoña, apparently Biscay’s most powerful church in medieval times, on the hill above the old town. This church (the current building early 16th century, apart from the baroque spire) is built in a typical Basque style which can be found all over the Basque country, with a tall, square, hall-like nave – like the Germanic ‘hallenkirche’. The church at Begona can be seen in many views of the city, nestled on the top of the hill over the river. Once surrounded by green hills, it is now in the middle of a residential suburb. Down the hill, by one of the gates into the old town, the Portal di Zamudio, pilgrims would next come to Santos Juanes, with its attached convent, now the Basque Museum. Next they would reach the church of St James – Santiago – the 15th century cathedral (with a 19th century façade) in the centre of the old town – very small for a cathedral, and not originally built as a cathedral, but a fine building. This church has the covered porch and arcading that is very typical of Basque churches – presumably because of the rain that falls on 50% of the days of the year. The city´s earliest church, however, and the one pilgrims would encounter as they left the city en route to Santiago, is San Anton, which occupies a crucial site by the medieval bridge and market place. Like many Basque churches, too, it has had a Baroque bell-shaped dome added to the tower. Nearby there is also the church of the convent of the Encarnacion, an atmospheric place where concerts of early music in Bilbao are generally held. After leaving Bilbao, one would work through the meadows where the new town is now built, passing the church of San Vicente And on to the town of Portugalete by the sea at the end of the estuary: These tall, buttressed churches stand at the centre of most Basque towns. Here is another one in the town of Elorrio (near the mountains in the centre of Euskadi): Here's one in Gernika: And one at Vitoria:

|

Bilbao Bloggings

A year in Bilbao Archives

September 2013

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed