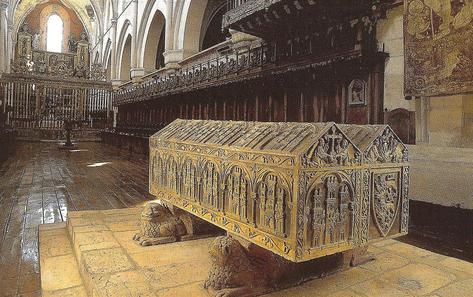

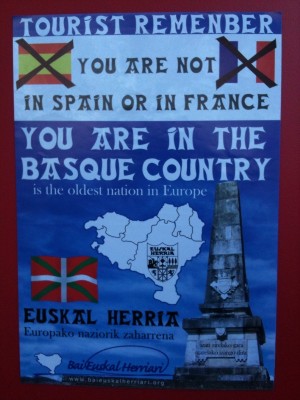

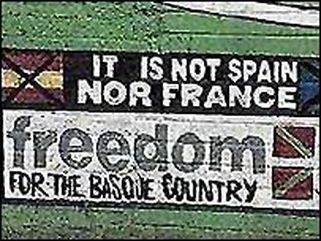

This was our only trip into Castile, the central region of Spain which was the heartland of the Spanish kingdom for hundreds of years. Burgos – the medieval capital of Castile – with its grand medieval heritage (magnificent cathedral, royal monasteries, enormous castle and so on), its open landscapes, and its lack of industrial hinterland – felt quite different from the grittier, less fancy, mountainous Basque Country, despite being only a few miles south of it. On the other hand, like many cathedral cities, it also felt very much as though it had had its age of splendour and was living off past glories.

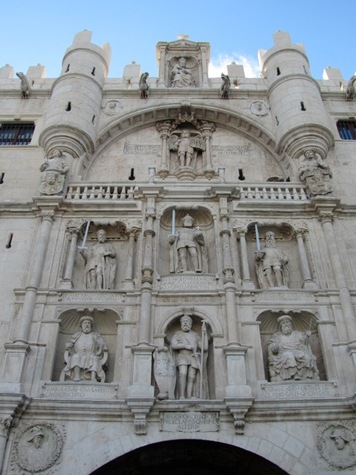

The fantastic cathedral – the first great Gothic cathedral of Spain, built in imitation of the French cathedrals – dominates the city…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed